St. James Cathedral has a big place in my life. Seventeen years ago, my husband Norman and I were married here. Over the years, I’ve been a choir member, a reader, and a sidesperson. And for four years, Norman and I were neighbours. We lived in the condo just to the north and we used to set our watches by the bells.

I’m not, however, what people call a ‘cradle Anglican’. When I was a child, my family attended St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church at King and Simcoe, just down the street.

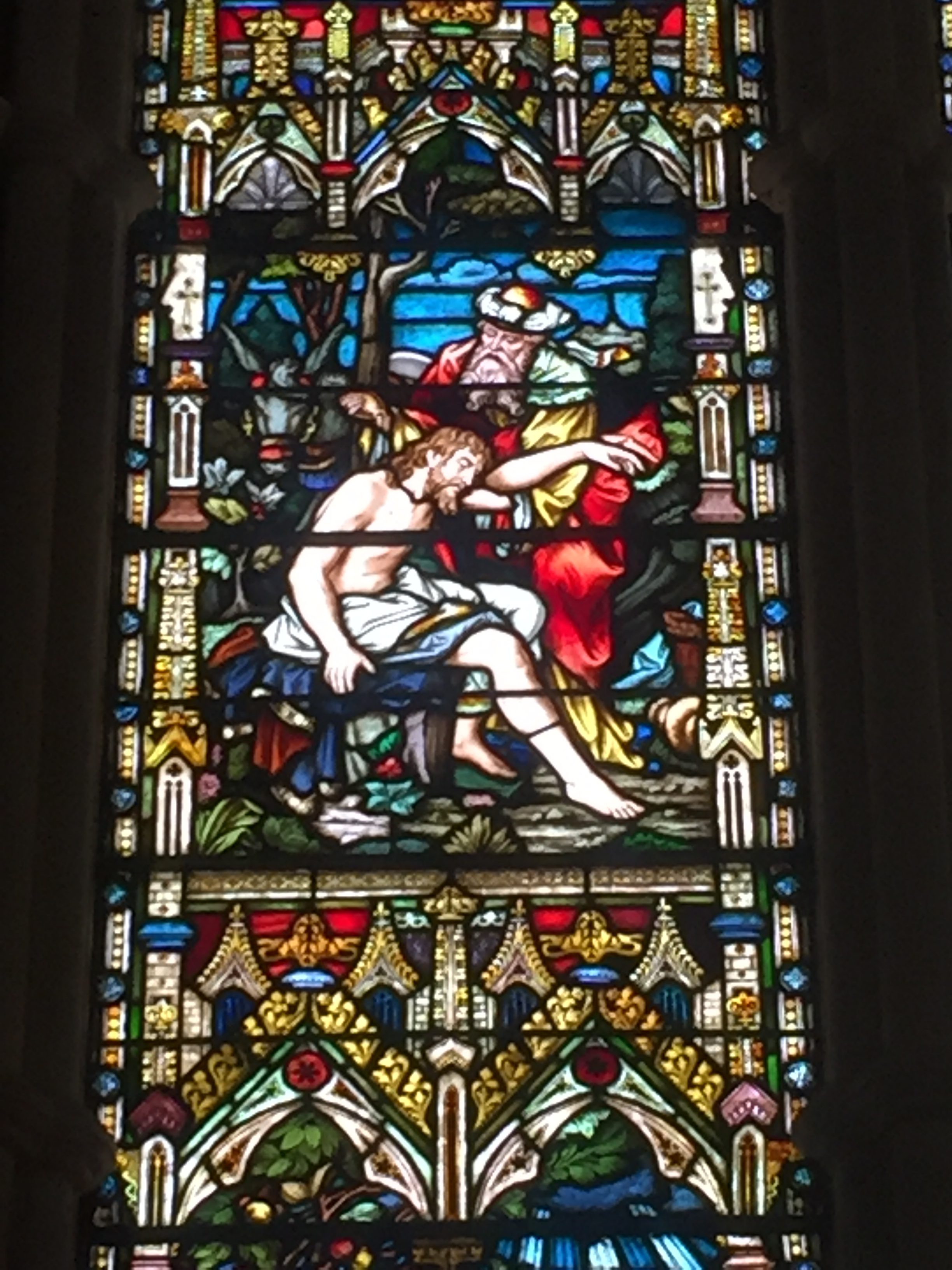

Now, whenever I enter St. James, I see a familiar face in the chancel. To the left of the main window, is a window that illustrates six of the parables. On the left side, in the middle, we see a nearly naked man being propped up by another man, who is dressed in rich robes and holding a small bottle.

The exact same image can be seen at St. Andrew’s, in the middle of the chancel. It’s larger there, with more detail, but it’s the same two people in the same pose.

The funny thing is – all those years at St. Andrew’s, I thought I was looking at the lifeless body of Christ after his crucifixion. I thought the man behind him was Joseph of Arimathea, holding embalming oil and preparing Christ for the tomb. It made perfect sense to me.

Then I saw the same image here, in the context of the other parables, and realized that the man in robes is the Good Samaritan, who is pouring oil on the wounds of the man who was set upon by robbers. I even noticed that there’s a donkey on the left side, as mentioned in the parable.

It’s an important parable, because it’s the one Jesus told after being asked, “Who is my neighbour?”

When the newspapers use the term “Good Samaritan,” they usually mean any passerby who stops to help someone in an emergency.

But there’s much more to the story. The Samaritans disagreed with the Jews on many points of religion. So in coming to the aid of a wounded Jewish man, the Samaritan was crossing a religious and tribal divide. That’s crucial.

Like me, many of you grew up in different religious traditions, either slightly different or really different, or with no religious tradition at all. And yet here we all are, singing the same hymns and saying the same prayers.

But my original mistake was instructive. Jesus said, “Whatever you did for the least of these my brothers and sisters, you did for me.” So I wasn’t completely wrong. I saw Jesus in the window, and I still do. That’s part of my connection to the image.

For all of you, wherever you come from, and whatever tradition you grew up with, you can probably find something familiar here. A fellow sidesperson said he found familiar names in the memorials. Others hear something familiar in the music, because we draw on such a wide range of musical sources.

So that’s what St. James means to me: it’s a place where people from many different traditions come together and connect.

Philippa Campsie